The 1972 world chess championship match served as a unique conflagration of global political affairs and the game on 64 squares. There’s a reason why it was referred to as the Match of the Century: The Soviet system thoroughly dominated the chess world at the time and the political elite pushed great resources into the game to showcase their intellectual superiority over the West, making the matchup a Cold War special.

From 1947 onwards, the world chess championship matches were Soviet internal affairs and the rankings lists were dominated by the red flag. No one even came close to challenging their hegemony and there was no sign that anyone would even come close to doing so.

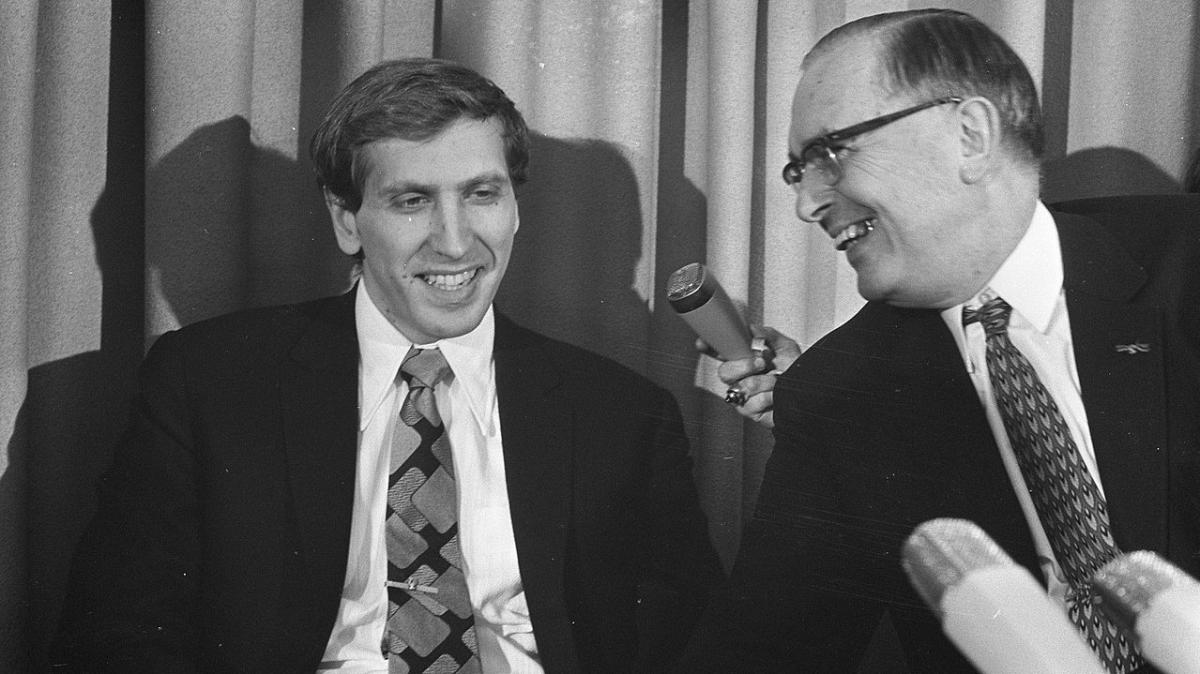

Enter Bobby Fischer, the lonely American genius, one of the most controversial figures in the game, and a mercurial talent with a meteoric rise. Nudged forward by Henry Kissinger, then a national security advisor and soon to become the 56th Secretary of State, and cheered on by a new generation of chess fans, he went on to win the most momentous of world chess championship matches in modern history against Boris Spassky in 1972. He single-handedly dismantled the Soviet chess machine and rose to the top of the chess world, only to forcefully fade away and take a dark turn in life.

Cold War on the chessboard

For modern fans of chess, it’s tough to imagine just how dominant the Soviet Union’s slate of elite players was in the game. Between 1948 and 1972, all world champions and their challengers hailed from the Soviet bloc, making the highest level of chess a strictly internal affair for the regime—and a great propaganda point.

Fischer’s meteoric rise changed all this. Emerging from nowhere, with little in terms of supporting background, the young American broke records and crushed opponents left and right, wreaking havoc in the chess world. Even then, there were the occasional bust-ups, accusations of collusion, resignations, and retirement, but even Bobby Fischer couldn’t stop Bobby Fischer from qualifying for the 1972 world championship match, securing his challenger spot in dominant style.

First, he crushed Mark Taimanov, one of the leading Soviet chess players at the time by a 6-0 score, then did the same to the Danish Bent Larsen, the strongest Scandinavian grandmaster before the recent emergence of Magnus Carlsen, arguably the greatest player of all time. The previous world champion, Tigran Petrosian, only managed to slow him down in a match that ended 6.5-2.5, setting up a fateful match between Fischer and the Russian Boris Spassky, the fifth consecutive champion to hail from the Soviet Union.

For the first time, Soviet officials had to negotiate with the world chess federation (also known as the Fédération Internationale des Échecs, or FIDE) and their American counterparts to find a suitable location for the match. Spassky was not going to play in the U.S. and Fischer was not going to go to the USSR. After an arduous process, Iceland’s Reyjkavík emerged as a compromise. Still, Fischer refused to agree to the terms, requiring the intervention of millionaire James Slater to increase the prize fund to $250,000, then the appeal of Kissinger himself to convince him to go.

In the end, a best-of-24 match was agreed upon, with three games scheduled for each week, where the champion would keep the title in the case of a 12-12 draw.

At the start of the match, Fischer had never won against Spassky, though he was still seen as the overwhelming favorite courtesy of his significantly higher Elo rating. He pushed too hard in an even endgame and made an elementary blunder, gifting a win to Spassky. He then refused to appear for the second game, demanding all cameras be removed from the playing hall.

It could have all ended then and there, but Spassky graciously accepted a request to play game three in a small back room. It was his biggest blunder of the match.

Fischer fulfills his destiny

Once Fischer sat back down at the chessboard, he never looked back. After a win in game three and a draw in game four, the American won back-to-back games, taking over the lead despite starting 0-2 down. His performance in game six was so spectacular that even Spassky joined the audience in applause after he resigned.

Fischer won again in the eighth and 10th games to gain a huge lead, only to suffer a dramatic loss in game 11 against Spassky’s deep and precise preparation against the Poisoned Pawn Variation in the Sicilian Defense: The retreating move 14. Nb1 led to the loss of Fischer’s queen and seemingly brought the match back in the balance.

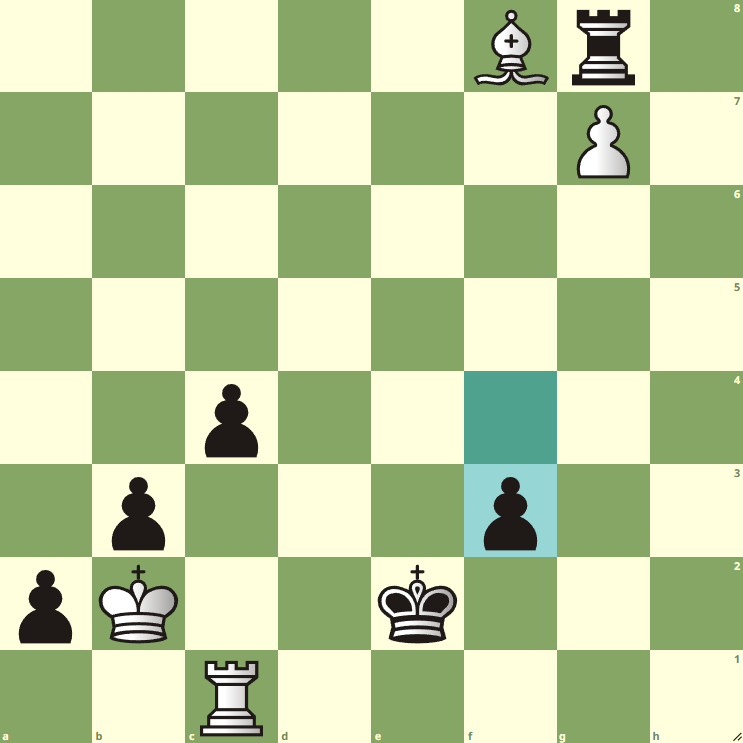

Instead, it was Fischer again who scored a decisive win, a legendary game on Aug. 10, 1972, where Spassky gave away a fairly easy draw after adjournment (back in the pre-computer era, overly long chess matches were paused and continued the next day, with both sides sealing their next move before leaving the playing hall to analyze the position in their hotel rooms), leading to a position where Black’s rook was completely trapped but had five pawns rolling down the board to overwhelm White’s.

There isn’t enough room here to discuss the permanent white noise of drama in detail that surrounded the match (in fact, full books were written about the subject—more on that in a bit). Fischer’s non-stop threats of withdrawing from the match and a never-ending stream of complaints about the organizers, the audience, the cameras, and everything under the sun was an unpleasant sideshow throughout the match.

Having now established a three-point lead, Fischer was more willing to accept drawish positions and Spassky also seemed content with just hanging in there. The drama would end 21 days later with game 21. Again, Fischer took the initiative with the Black pieces, employing an opening he’d never used before and a novelty that was new to the chess world on move eight. Though the players reached an even middle game, Spassky’s imprecise moves led to a big edge for Fischer by the adjournment on move 40.

By the morning, it was clear to everyone how the game and the match would conclude. In an unprecedented decision, Spassky resigned the game by telephone, which meant Fischer won the match by a convincing scoreline of 12.5-8.5, becoming the 11th world chess champion. It was the pinnacle of Fischer’s professional career and personal life, with a downfall the likes of which has rarely been seen in sports to follow.

Rejkyavík marked the last time Fischer would play an elite-level chess event. He demanded multiple format changes for the match scheduled for 1975 against Anatoly Karpov: the first player to reach 10 wins, draws excluded, would be the winner, and he’d keep the title with a 9-9 score. His first demands were accepted but the latter wasn’t (along with a refusal to commit to a potentially endless match), and Fischer resigned his title as a consequence.

He didn’t play another competitive chess match for almost 20 years, only emerging for an unofficial rematch with Spassky in 1992 that was bankrolled by a Yugoslavian millionaire. He won again, this time by a score of 10 wins to five, using the format that was rejected by FIDE back in 1975. Participation in the event violated international sanctions, however, and Fischer had to flee prosecution after the fact.

This perfect mixture of chess and politics, coupled with such magnetic personalities involved, made many interested in the seminal event, even among those who aren’t well-versed in the intricacies of elite-level chess competition.

Many have tried to unravel the enigma of Fischer and countless biographies have been written of his life. Of these, Frank Brady’s Endgame is perhaps the best and most thorough of them all. When it comes to the 1972 match itself, no book does a better job capturing the geopolitical kerfuffle and the individual drama than Bobby Fischer Goes to War by David Edmonds and John Eidinow, deeply detailing the rise and fall of both players, the allegations of the KGB and the CIA, the political skirmishes, and everything that went on behind the scenes and in front of the cameras.

Hollywood also had its own variation on the theme with 2014’s Pawn Sacrifice, a disappointing movie that does little to highlight the nuances of the affair. In spirit, the musical Chess comes closest to capturing the mood of this clash of the titans, though it only uses the 1972 matchup as a loose starting point of a very different story.

Most of the actors of the Reykjavík drama are long gone, but a few pieces still linger on the chessboard. Spassky is still alive, though no longer actively competing, like two of his seconds, Iivo Nei and Nikolai Krogius. No American has claimed the title since Fischer, though Fabiano Caruana came close in 2018 against Carlsen. The Soviet/Russian dominance faded after Karpov, Kasparov, and Kramnik. Though Russian pros still make up the bulk of the chess elite, the world championship title has been in Indian and Norwegian hands, respectively, since 2007.

FIDE hasn’t done much to commemorate the 50th anniversary of this legendary affair, but Carlsen has been positively Fischer-like with his demands about the upcoming match. The world chess championship matches of today bear little resemblance to the duels of Fischer’s time: Lately, it’s been a mere 12 or 14 games with faster tiebreakers to follow, featuring a lot of draws.

Fischer would no doubt be disappointed about the state of affairs, but he’d probably approve of Carlsen’s demands of more, faster games in the world championship match to force more decisive results. Perhaps he’d also smile knowing Carlsen copied his ultimatum: If the Norwegian’s requests aren’t met, he might resign his title, showing that even if history doesn’t repeat itself, it most certainly rhymes.

Published: Jul 11, 2022 04:25 pm