Skewers are a tactic in chess revolving around a strong piece and indirectly hitting a weaker, undefended target behind it. In many ways, they’re the opposite of a pin, and they tend to lead to an immediate win of material.

What is a skewer in chess?

Sometimes called a “reverse pin,” skewers are also about making use of two enemy pieces lined up in an unfortunate manner. By attacking a valuable piece in front, forcing it to move away, you expose the less valuable one behind it, ripe for capture.

There are two types of skewers: absolute skewers and relative skewers. Absolute skewers involve the king, which is, in effect, the most valuable piece in the entire game. They have no choice but to get out of the way when they’re attacked—meaning when your opponent gives you a check—and if they can’t get out of the way, you’ve got bigger issues than the loss of material because it means it’s checkmate and the game is already over.

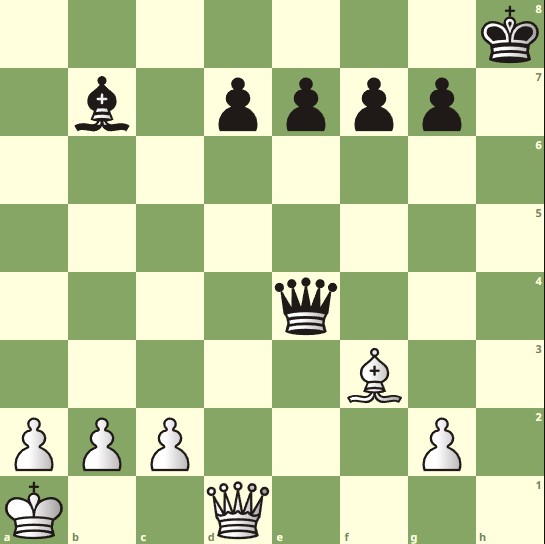

Relative skewers involve two non-king pieces. Let’s take a look at this example below:

By attacking the queen and forcing it to get out of the way, she exposes the bishop on b7 to attack. This wins material for White in the position. Of course, if the b7 bishop were protected, this tactic wouldn’t work at all: it’s important that you can actually win the piece you’ve exposed with your crafty move.

How to get out of skewers?

Usually, it’s too late by the time the skewer tactic is on the board, so prevention is the best approach. “LPDO,” or “loose pieces drop off,” as the chess advice goes: try to keep your pieces protected, preferably by pawns or other relatively inexpensive pieces instead of relying on the queen or the rooks on the frontline.

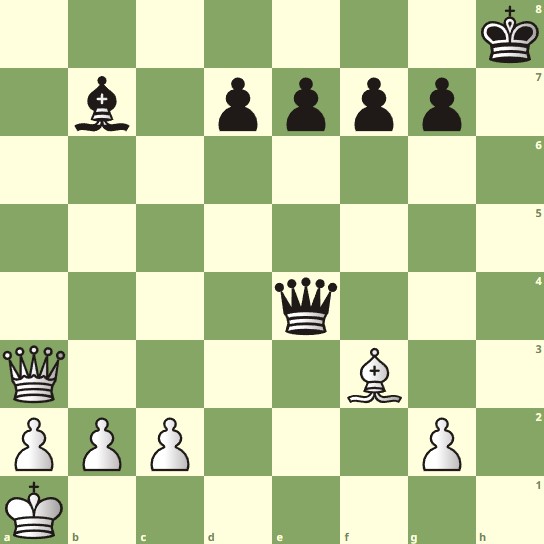

You can also get out of skewers when you have an even larger threat available to you. Consider the previous example with the white queen moved over to a3:

Here, Bf3 would be a terrible blunder because Black could play Qe1+ with checkmate on the next move. In this case, the skewer could simply be ignored. Even if there would be no mate to follow, stepping out of the skewer with check and forcing your opponent to react to the move you’ve made can often be enough to dismantle the threat.

Published: Apr 20, 2022 06:33 am