In chess endgames, it is of paramount importance to figure out whether your king can catch an unescorted enemy pawn running up the board before it promotes. If you’re inside “the square,” you’re good. If you’re outside of it, you can kiss your chances goodbye—with a few notable exceptions.

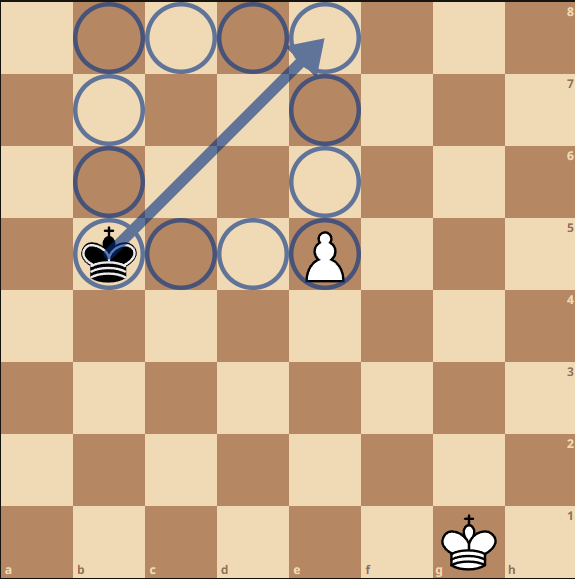

Since the Pythagorean theorem doesn’t apply on the chessboard (one diagonal move is the same as one forward move), the easiest way to calculate whether you can catch a pawn with your king is to draw an imaginary square on the board (just an imaginary one. Please don’t get your Sharpie out during play) like this:

Here, it will take White three moves to promote the pawn, which is just the time Black needs to get back with the king. Since the king is inside the square formed by the pawn and the diagonal to the promotion square, the position is a draw.

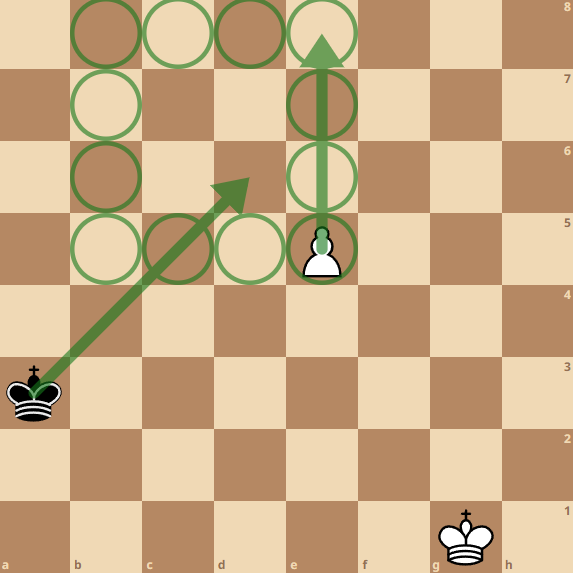

Let’s move the Black king back a bit to make it a win for White:

Now there’s no time to catch up and save the game.

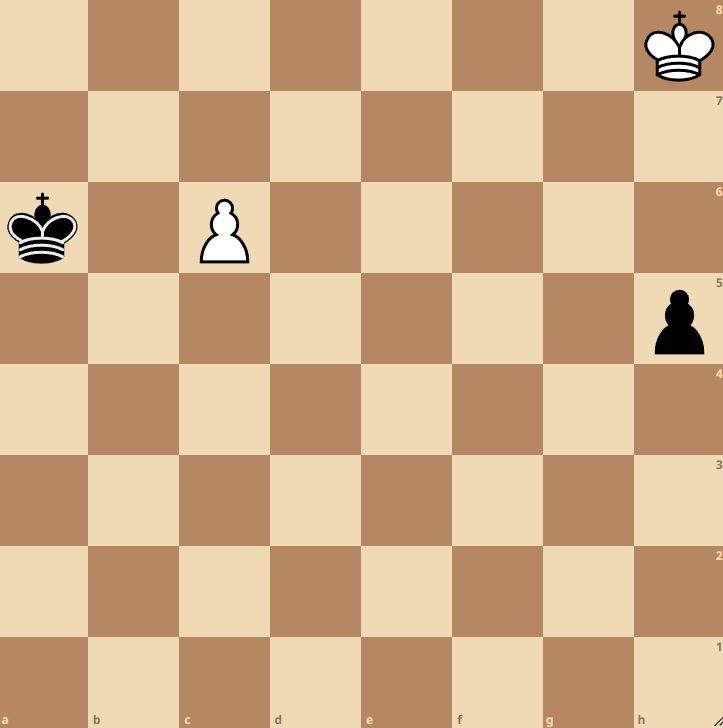

In rare circumstances, you can find ways to make up for a missing tempo or two. In this infamous endgame study by Richard Réti, the Black king is inside the White pawn’s square while the White king is hopelessly lagging behind—and yet, there is a miraculous way for White to draw the position.

After 1. Kg7! And Kf6 and Ke5, White will either escort its own pawn to promotion or catch up with the h-pawn, getting inside the square as Black uses to tempi in capturing White’s c6 pawn.

Published: Nov 30, 2022 08:23 am