Frostpunk 2 is cold and dark. And I don’t mean cold and dark like your fridge when the door’s closed. I’m also not talking about the black soot and white ice of its 19th-century ice age setting either. What I’m saying is that Frostpunk 2 is emotionally cold and dark.

During your tenure as the “Steward” of a small population of survivors struggling to survive the mother of all cold snaps, you routinely have to make decisions that, whichever choice you make, result in the suffering, misery, and death of thousands of people. And it’s all just a part of the job.

To give you just one of a great many examples, at some point, you have to decide on a city-wide policy regarding funerals. If you allow every stiff the dignity of a ceremonial send-off, your populace will be happier in the short term. But if you decree that everyone has to be tossed straight into the generator furnace the moment they’ve popped their clogs, fewer of your people will freeze to death in the long run. One thing’s for sure: Keeping everyone happy and alive is never, ever an option in Frostpunk 2.

Our own worst enemy

I’ve played a lot of strategy/management games in my time, so I can say with some confidence that there’s never been one with such a strong sense of atmosphere, tone, and narrative as Frostpunk 2 (except maybe the original Frostpunk, of course). And this is no accident. Developer 11 bit studios has repeatedly said that in Frostpunk 2, “the greatest threat is no longer nature itself, but human nature,” and the game absolutely delivers on this promise.

While in the original game, you played as a kind of autonomous dictator wrestling with their conscience (which was traumatic enough), this time, you have a variety of ideologically opposed communities to contend with. The way each one of them prioritizes its own tribalistic ideology over rationality, fairness, and the long-term survival of the whole population is a thought-provoking and depressingly familiar reflection of how people behave in the real world. And you, dear player, are caught in the middle of it.

This means that in Frostpunk 2, you’re not just juggling the deployment of a very limited supply of resources; you also have to maintain a balance among the values and priorities of your city’s population. If your decisions go against the wishes of one community too many times, then that group (even if it represents a small minority of the overall population) can end up causing a huge amount of trouble for everyone. On the flip side, if you manage to make one community particularly happy, then they’ll hold rallies in your favor, which result in various perks like a boost to cash flow or workforce. But good luck keeping them happy for long.

Community service

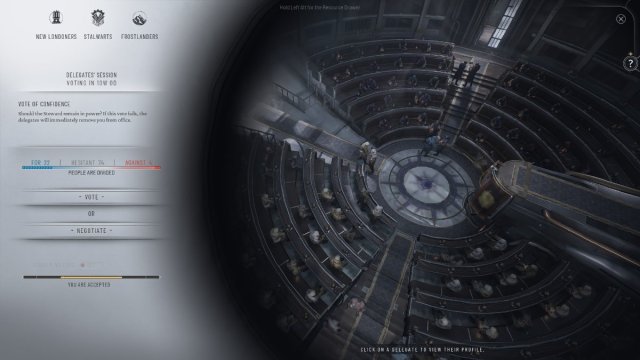

Pretty much every decision you make affects your approval ratings among these communities, but there’s also a major new gameplay feature that explicitly deals with the political layer of the game, namely the Council Chamber. Every 10 weeks, you can propose a new law. But for that law to pass, it has to win a majority vote among the 100 delegates representing the different communities in your city. Every new law has more upsides than downsides, but there always are downsides, and true to human nature, delegates always focus disproportionately on the downsides—and have opposing views on which downsides are the worst.

This means you sometimes need to do a bit of negotiating to get a new law through, and that entails making a promise to an on-the-fence faction in return for their support. That promise might be to construct a particular building, research a particular technology, or propose another law of that community’s choosing. In this way, the politics of Frostpunk 2 is as tightly woven into its gameplay mechanics as it is into its narrative themes. It lends the game a new layer of depth and complexity—and a new way to give you, the player, a headache. And in Frostpunk 2, in a weird sort of way, headaches are all part of the fun.

Harsh, and also unfair

Frostpunk 2’s belief in the value of tough decisions applies not just to how it’s played, but also to how it’s designed. By that, I mean the game can be just as harsh on you as you sometimes have to be on your city’s population. At the start of the game, there are a couple of text pop-ups, one warning you that the game is challenging and that you’re just going to have to accept that, and another advising you to play the Story before you try the new Utopia Builder mode because the Story mode will teach you how to play the game.

But the Story mode is pretty quick to remove the training wheels, which means it avoids getting bogged down in hours of tutorials but also that by the time you reach its second half, you and your city will likely be woefully unprepared for the incredibly steep rise in difficulty to come. At this point, I felt like I had no idea what was happening or why, and the game suddenly got extremely frustrating and stressful. The Story mode is one long scenario, so all the time and resources you wasted early on (when things were relatively easy) make it even harder when the difficulty ramps up.

But when I gave up and decided to start a new city in Utopia Builder mode—which is great and adds a lot of value to the package—I discovered that I had in fact learned a lot of lessons that I could apply to the early stages of the game. And at that point, I started having a lot more fun.

So, while I’d say there are definitely flaws in the onboarding, pacing, and balancing of the Story mode, Frostpunk 2 still offers an engaging and rewarding overall package for city-building fans able to accept harsh punishment and willing to give up and start again from scratch.

- Superb atmosphere and tone

- Tightly designed mechanics

- Genuinely thought-provoking

- Jagged learning curve

- Can get stressful and depressing

Published: Sep 17, 2024 12:05 pm